Andrew Sarris and Auteur Theory: What If Brad Bird Directed Brave?

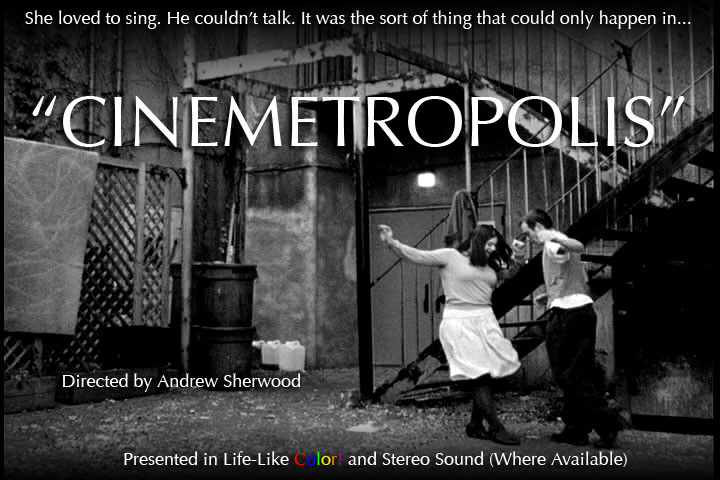

My favorite shot in Cinemetropolis comes toward the beginning of the dance scene you can see on the Media Page. It's the one that starts with a close up of the drainage pipe and zooms out to reveal Melisma and Sordino dancing in the alleyway. I wish I could take credit for that shot, but I can't. It was my director of photography, Kevin Warnecke, who came up with the idea on set. I had originally wanted to do two shots- one of the pipe, and one of the dancers, and Kevin suggested combining them. I thought it was a great idea that would save us time, and we got the shot.

This anecdote came back to me when I heard that Andrew Sarris had passed away a few weeks ago. The Internet became a buzz with the usual obituaries and retrospectives, including this one from David Bordwell. Sarris is best known for popularizing "Auteur Theory" in the U.S., after it had been developed by the French magazine, Cahiers du Cinema.[ref] He's also the namesake of the villain in Galaxy Quest. [/ref] Simply put, Auteur Theory says that a movie's director is the auteur, or author of a movie, equivalent to a painter, composer or novelist.

This anecdote came back to me when I heard that Andrew Sarris had passed away a few weeks ago. The Internet became a buzz with the usual obituaries and retrospectives, including this one from David Bordwell. Sarris is best known for popularizing "Auteur Theory" in the U.S., after it had been developed by the French magazine, Cahiers du Cinema.[ref] He's also the namesake of the villain in Galaxy Quest. [/ref] Simply put, Auteur Theory says that a movie's director is the auteur, or author of a movie, equivalent to a painter, composer or novelist.

A common critique of this idea is that giving exclusive credit to the director ignores the collaborative nature of filmmaking. Producers, writers, actors, etc. all work on a movie together, each contributing a piece to the final product. Jim Emerson, in his writeup, says this wasn't what Sarris really meant- he just gave attention to a few directors he thought were good.

Sarris revised and refined his ideas over time, and I'll give him the benefit of the doubt. Even so, the worship of the director has given us those pretentious and undeserved "A Film By" and "A NAME Film" credits for everyone and his brother.[ref] In my book, to get one of those, you need to do everything, including act every part and develop the negatives yourself. [/ref] I've also been guilty of thinking of movies mostly in terms of who directed them.

This is not to say we shouldn't study the canons of various directors. We should, but I'd like to look at how different people or things might put their own unique stamp on a movie, even if they aren't the director. While in school, I wrote a major paper arguing that Pixar Animation Studios should be considered an auteur in its own right, given the common elements that show up in its work.

Right around when Sarris passed away, I went to see the newest Pixar release, Brave. Two elements I had noticed from before were present here: a protagonist or sympathetic character as a source of conflict rather than the villain[ref] Compare Merida's wish with how Flik destroys the food supply in A Bug's Life, Boo invades Monsters, Inc., Buzz becomes Andy's favorite toy in Toy Story, and Russell ruins Carl's trip in Up.[/ref], and two characters who must put aside their differences in order to work together.[ref] Woody and Buzz, Carl and Russell, Sulley and Mike, Marlin and Dory from Finding Nemo, WALL-E and EVE, Remy and Linguini from Ratatouille, etc.[/ref]

Two elements I had noticed from before were present here: a protagonist or sympathetic character as a source of conflict rather than the villain[ref] Compare Merida's wish with how Flik destroys the food supply in A Bug's Life, Boo invades Monsters, Inc., Buzz becomes Andy's favorite toy in Toy Story, and Russell ruins Carl's trip in Up.[/ref], and two characters who must put aside their differences in order to work together.[ref] Woody and Buzz, Carl and Russell, Sulley and Mike, Marlin and Dory from Finding Nemo, WALL-E and EVE, Remy and Linguini from Ratatouille, etc.[/ref]

While writing this paper, I ran into the interesting case of Brad Bird, who infused themes of individualism vs. collectivism into his work that weren't present in other Pixar movies. In a world of Society and its Outsiders, Bird, an individualist, is with the Outsiders. Society must accept them, and the Outsiders don't compromise to earn approval. Consider his Author Tract from Ratatouille, where caustic food critic Anton Ego proclaims "a great artist can come from anywhere." Even a rat can be "the finest chef in France."

It occurred to me that Brave would be a very different movie had Brad Bird been the one to direct it.[ref] The actual directors were Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman. [/ref] Had Bird's individualism been a theme, I suspect Merida's strong-willed rebellion would have been more accepted. Her parents, especially her mother, would have learned to love her unconditionally, and let her follow her own path. Instead, the story shows us, and Merida, the chaos that can result from her rejecting all tradition. Unlike Ego, who accepts Remy for who he is, Merida and Elinor make like Woody and Buzz- and compromise.

This, I think, is the more interesting take on teenage adolescence, and one of the reasons Pixar is one of the most talented auteurs working today. Of course, Brad Bird is a smart guy, and I expect him to examine the problems associated with individualism in future projects. This, to me, is a useful application of auteur theory, not simply worshipping a Pantheon of Olympians. I haven't read all of Sarris's work, but I hope, and suspect, from his retrospectives, that this is more what he had in mind. If so, I can get behind him wholeheartedly.